They want to tell other banks and credit unions what they can and can’t do. There’s no reason for it. Maybe they don’t like the credit union value proposition. Or don’t want other banks to have more options. Maybe they don’t believe in free markets and competition.

SB177 would block state-chartered banks from selling assets to a credit union. This makes the national charter more attractive. Over time, fewer banks would use the Utah bank state charter (as has already happened with credit unions), and oversight of Utah’s financial assets would move toward the federal government. Wouldn’t local control be better?

Additionally, with fewer competitors for the purchase of state bank assets, the price of those assets drops. This effect is convenient for banks that are prospective buyers of other banks. Without credit union competition, they could purchase state banks for a lower cost. Wouldn’t more competition among buyers be better for banks looking to sell?

When a bank sells its assets to a credit union, everyone wins. Taxpayers. Credit union members. Consumers. Even bank owners.

They want to tell other banks and credit unions what they can and can’t do. There’s no reason for it. Maybe they don’t like the credit union value proposition. Or don’t want other banks to have more options. Maybe they don’t believe in free markets and competition.

Whatever the reason, just as they did two decades ago, they’re trying to use government to limit the options of banks and their owners, and credit unions and their members.

Twenty years ago, a few prominent bankers wanted to put more limits on credit unions—and just like last time, now they’re trying to use the Utah State legislature to do it.

Back then, to further their own profits, they told the public and legislators that putting credit unions in a legal box would stop their growth and benefit the public.

They were wrong. In fact, the only result of those efforts was costing the state a great deal of sales tax revenue.

Since then, Utah’s credit unions have proven resilient and are serving more Utahns than ever.

A bill in the Utah state legislature, SB 177, would make it illegal for a state-chartered bank to sell more than 10% of its assets to a credit union.

However, when a bank sells its assets to a credit union, everyone wins. Taxpayers. Credit union members. Consumers.

Why might a bank want to sell assets to a credit union?

Nobody loses when a bank merges with a credit union — except for people who’d rather not have credit union competition in their market.

The intended purpose of this bill is to prevent the sale of bank assets to credit unions.

However, it would have several negative effects on the financial services in Utah—to satisfy just one or two prominent bankers.

First, this bill weakens the state bank charter when compared to the federal charter.

Because the bill applies only to state-chartered banks, exit strategies of state-chartered banks would become more limited, and the state charter becomes less attractive than the federal charter.

The result? Fewer banks use the state charter. And banks wanting to sell assets to a credit union will need to switch to a federal charter.

If passed, SB 177 makes the state bank charter weaker, less attractive. Federal government gains more power. State government loses power.

This is like what happened with credit unions 20 years ago—at the request of these same few bankers: the state legislature weakened the credit union charter. Those few bankers said that credit unions would be subject to the more restrictive state laws, unable to do anything about them. But in fact, out of necessity, they switched to a federal charter, thereby escaping the punitive state laws. Those few bankers sold a bill of goods to the state legislature, and it cost the state’s coffers millions of dollars of sales tax.

Legislators and Utah bankers might well consider: if one or two bankers not subject to this law start pushing legislation against Utah state banks, how far will they take it? Will they continue to push legislation that puts Utah banks at a disadvantage, and national banks at an advantage? What’s to stop them?

It’s best to stop them now, before they gain any more momentum.

Second, the bill promotes the formation of banking deserts in rural Utah.

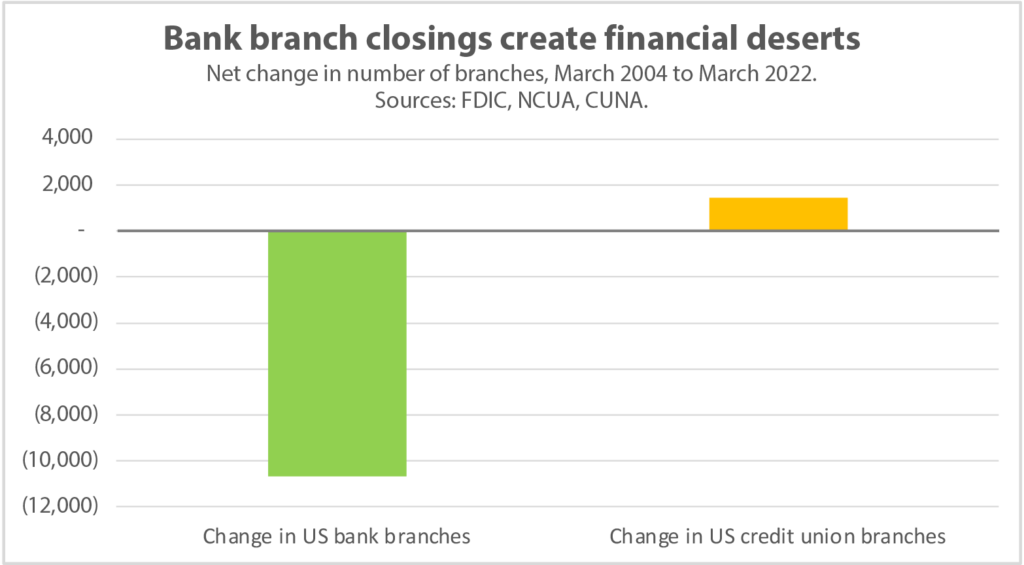

Banks across the country are closing branches and therefore reducing physical access, generally. However, credit unions increased the number of branches.

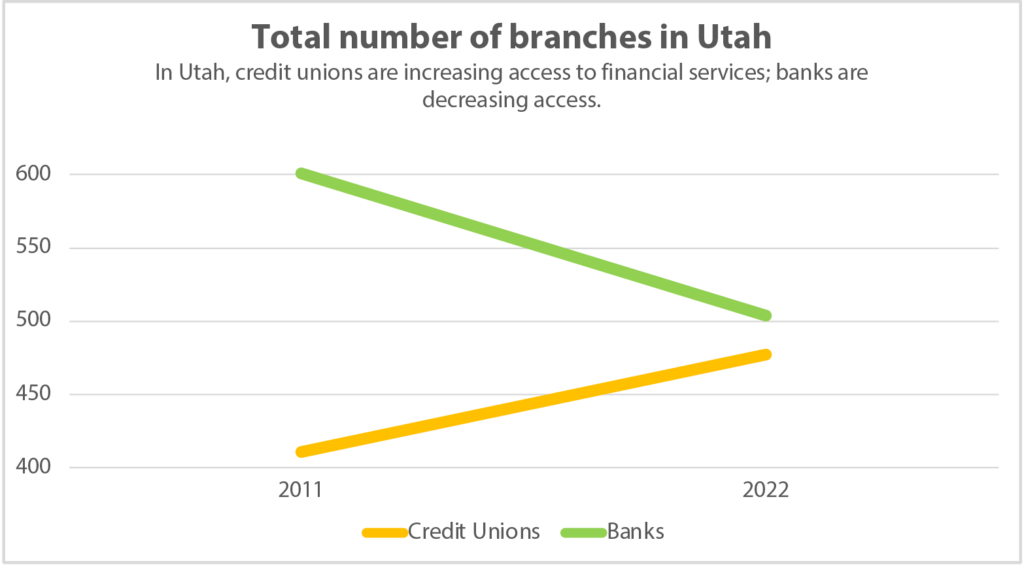

This is certainly the case in Utah.

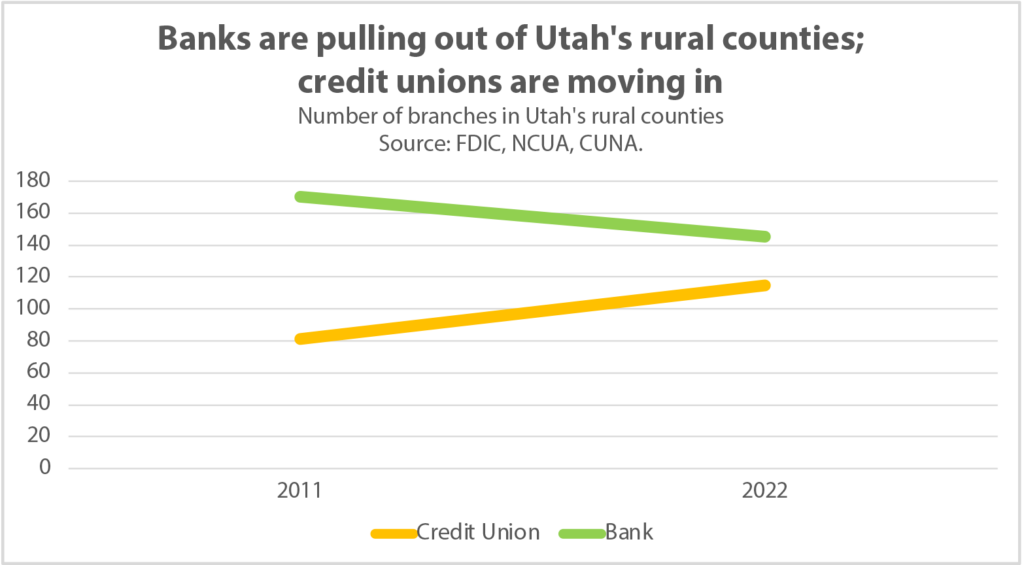

Importantly, this trend is found not only in heavily populated areas of Utah, but also in rural areas. Between 2011 and 2012, the number of branches in rural Utah has decreased for banks, and increased for credit unions.

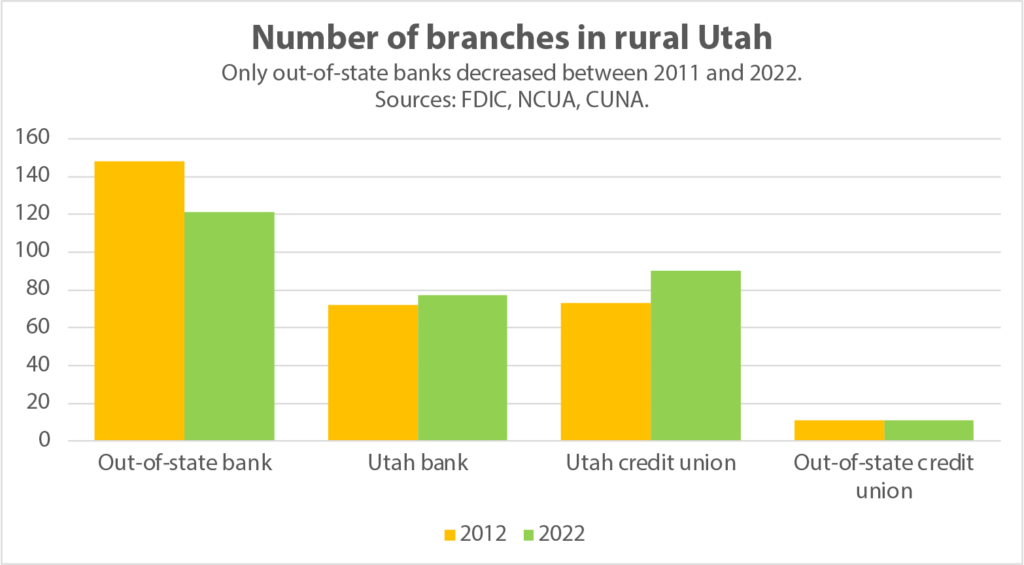

Splitting the data between Utah institutions and out-of-state institutions reveals some interesting information. As it turns out, when you compare out-of-state banks, Utah banks, Utah credit unions, and out-of-state credit unions, only one of the four types of financial institution had fewer branches in rural Utah in 2022 than in 2012.

You guessed it, out-of-state banks.

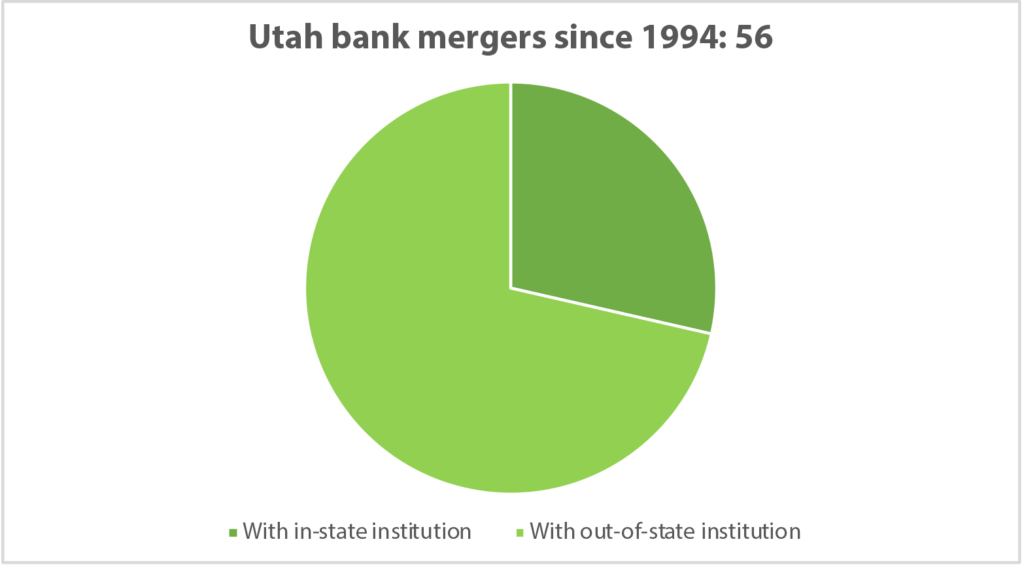

Notably, Utah banks tend to merge with out-of-state banks.

Long story short: Utah banks tend to merge with out-of-state banks, which tend to close branches in rural Utah, spreading banking deserts.

Wouldn’t it be better if it remained an option for Utah banks to merge with credit unions, which are working to decrease financial deserts in rural Utah? Such an option could reduce the spread of banking deserts in Utah’s rural areas.

Below is the story of how Grand County Credit Union (now Desert Rivers Credit Union) opened a branch in Green River, Utah, after the out-of-state bank closed its branch.

Their arguments are—at best—only half truths. A few key bankers, who plan to never sell assets to credit unions (and whose banks conveniently wouldn’t be subject to this law) just don’t want credit unions to grow and succeed, even at the expense of other bankers.

Here’s some more information to give you a bigger picture:

So, why this legislation? A few powerful bankers are upset that credit unions have limited their earnings over the years, and want to poke credit unions in the eye—at the expense of other bankers and credit union members.

The confounding thing about this legislation is that by limiting a credit union’s ability to purchase bank assets it also limits a bank’s ability to sell assets to a credit union. This bill hurts Utah’s state-chartered banks by reducing their options!

So why do bankers want it? We don’t believe most of them do.

We think that one or two prominent Utah bankers are bent out of shape over past and future competition, and they’re pushing SB177 at the expense of everyone else—credit unions, state-chartered banks, bank owners, credit union members, consumers, and ultimately all Utahns.

So, tell your legislator that you won’t stand for them supporting a few powerful people over everyone else. Let them know that the special interest of the few is not as important as the benefits of millions of Utahns.

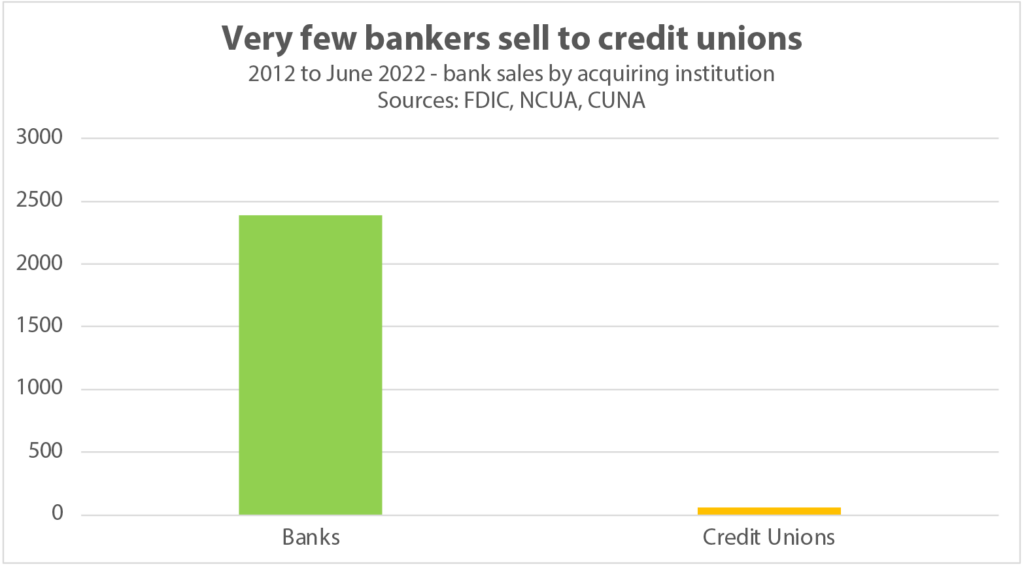

No. Not many do. From 2012 to June 2022, there have been 2,448 bank sales. 60 (2.45%) of those have been to credit unions. Not one of them has involved a Utah bank or a Utah credit union.

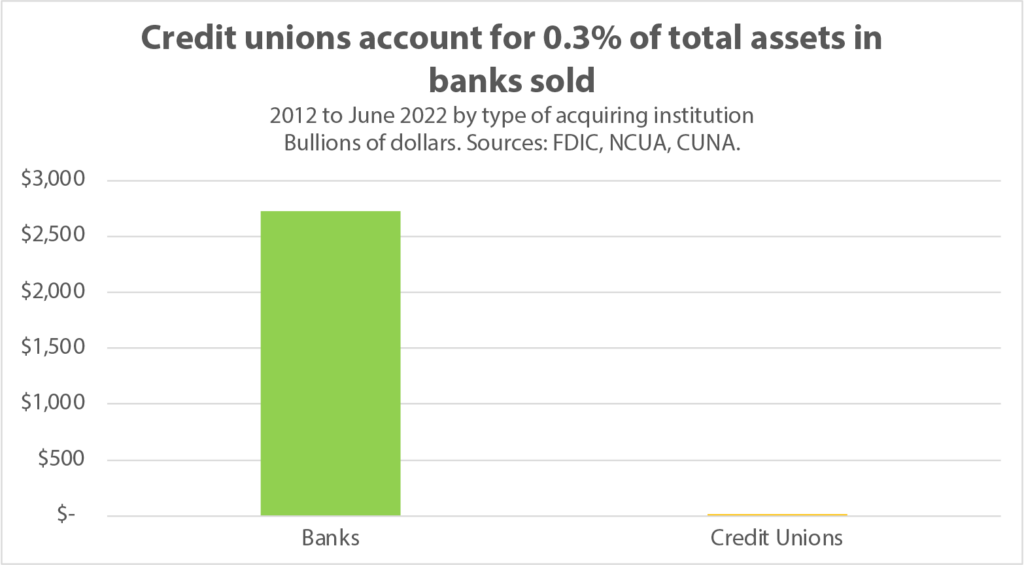

Those 2.45% of sales only account for 0.3% of assets sold.

Great question. The best we can come up with is that one or two prominent bankers still harbor ill will toward credit unions and the competition they represent in the market, and simply want to make a point.

But making that point comes at a cost to other bankers, credit unions, and all Utah consumers.

It’s all about standing up against narrow, powerful special interests that don’t benefit Utah communities — especially rural areas.

From what we can tell, SB177 is being driven by a few prominent bankers as a continuation of actions taken 20 years ago. Ultimately, these folks don’t appreciate competition in the consumer banking industry (it limits their profits), and legislation is their preferred way to stifle it.

But because No Utah banks have sold assets to Utah credit unions, their reasoning must be theoretical and philosophical. It’s policy enacted without reason or purpose. That’s not the Utah way, as we understand it.